There are 60+ species of Legionella. Only one is a serial killer.

Legionella pneumophila

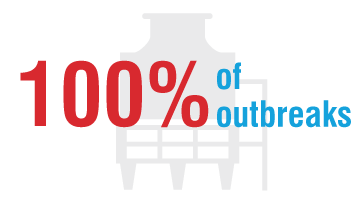

Data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) show that all outbreak fatalities have been caused by L. pneumophila.1, 2, 8-11

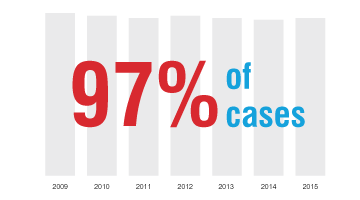

The ECDC’s clinical culture data shows that L. pneumophila causes nearly all cases of Legionnaires’ disease, year after year.3

Data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) show that L. pneumophila has been the only cause of outbreaks in U.S. cooling towers.1,2

Ready to add Legionella testing to your water management plan?

Locate a laboratory that uses the Legiolert Test for accurate, confirmed culture results for Legionella pneumophila in just 7 days.

Are you up to date on the new law in New Jersey?

Get the facts on this new law that requires certain buildings in New Jersey to test for Legionella.

Protect your community from Legionella pneumophila

Evidence shows that places testing regularly for L. pneumophila reduce the risk of Legionnaires' disease.

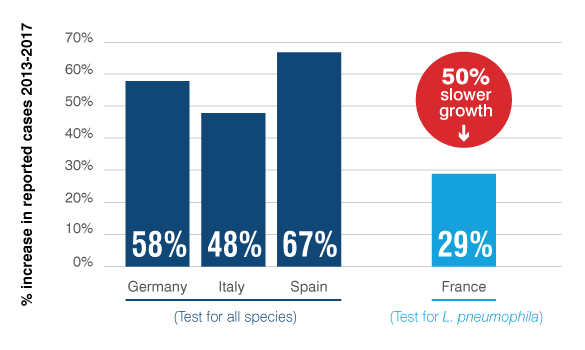

Increases in Legionnaires' disease cases are slowed when L. pneumophila is routinely tested

In France, mandatory L. pneumophila testing for building and cooling tower water has led to case rates increasing 50% slower than in European countries that test for all Legionella species. Legionnaires’ disease cases in France rose only 29%, compared to 58% growth across 17 European countries.4

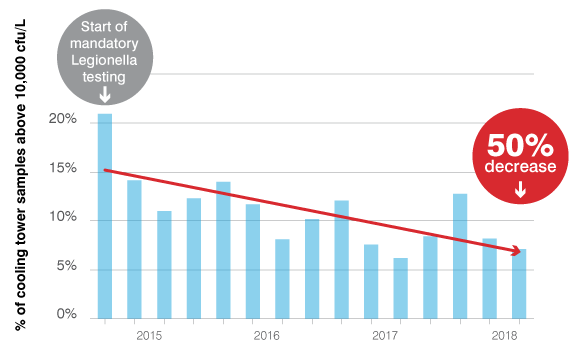

Routine L. pneumophila testing reduces the risk of cooling tower outbreaks.

Since Quebec mandated routine testing for L. pneumophila, the number of cooling towers with contamination above the action limits has dropped by 50%.5

Why look only for L. pneumophila?

Legionnaires’ disease is fatal in one out of ten cases, yet it is highly preventable.

The European Centers for Disease Control has collected data from cultures of 4,719 patients over seven years across 17 countries and found L. pneumophila causes 97% all cases of Legionnaires’ disease cases.3

Add L. pneumophila testing to your water safety management plan

Receive a free consultation on your water safety management plan or testing protocols.

Commonly asked questions about L. pneumophila and Legionnaires' disease

Legionella pneumophila is a gram-negative, aerobic bacterium that was isolated and named after the first recognized outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in 1976. It is one of more than 61 strains of Legionella bacteria, which are widely found in natural and artificial aquatic environments, soils, and composts.6 Legionellae can grow intracellularly in protozoa, and some strains have infected humans. L. pneumophila causes 97% of Legionnaires’ disease cases and 100% of deaths from outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease.1–3, 8–11

Culture Confirmed Legionnaires' Disease Cases Reported to the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control

Detecting this deadly strain can be challenging, as L. pneumophila can appear in different forms and can easily be obscured by competing bacteria in traditional spread-plate cultures.7

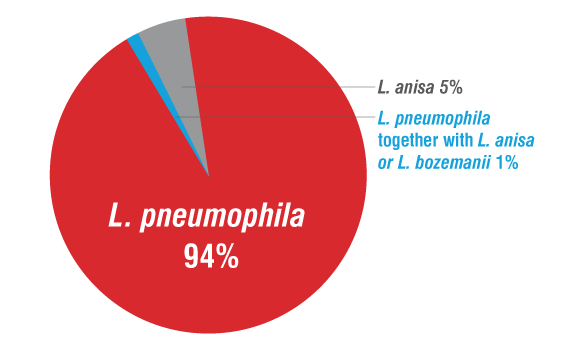

Legionnaires’ disease is fatal in 1 out of 10 cases, yet it is highly preventable.17 L. pneumophila causes 97% of Legionnaires’ disease cases and has caused 100% of deaths from documented outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in the United States. Testing for L. pneumophila ensures your facility’s water safety management plan is effectively controlling this risk. L. pneumophila is the most common and clinically relevant species of Legionella found in building water systems (94%). Measures to control L. pneumophila also control other Legionella species that may be present.1–3, 8–11

Legionella species found in 771 Legionella positive samples from 233 building water systems12

The bacteria are transmitted when contaminated water is aerosolized (e.g., through water sprays, jets, misting, showers, whirlpool spas, decorative fountains, ice machines). Infection occurs when people inhale contaminated air or aspirate contaminated water or ice.

Likelihood of illness depends on the concentration of the bacteria in the water source, the production and dissemination of aerosols, factors such as the age and health of the person breathing in the bacteria, and the virulence of the strain of Legionella. Legionella pneumophila is the most virulent species of Legionella, and within L. pneumophila, serogroup 1 is the most common cause of disease, although all serogroups of L. pneumophila are considered dangerous. The dose required to produce infection can be assumed to be low for susceptible people, as illnesses have occurred after short exposures and at distances of 3 km or more from the source of outbreaks.5,13,14

Legionella pneumophila is the primary cause of Legionnaires’ disease. This one species is responsible for 97% of cases and 100% of deaths from outbreaks of the disease.1–3, 8–11

Culture Confirmed Legionnaires' Disease Cases Reported to the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control

Legionnaires’ disease cases in France, which requires monitoring specifically for L pneumophila, increased at only half the rate of Legionnaires’ disease case increases across Europe between 2013 and 2017. Legionnaires’ disease cases in France rose only 29%, compared to 58% growth across 17 European countries and rates of between 48% and 67% for countries with regulation requiring regular testing for Legionella species.4

The U.S. and Canada have very high standards for water quality. In the U.S., all water distribution systems must meet the requirements of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Safe Drinking Water Act, including maintaining disinfectant levels and routine testing for various microbial and chemical parameters. However, drinking water is not sterile. Low levels of Legionella pneumophila can be present even in a well-run system that meets all national- and state-level standards for water-quality. These low levels can become dangerous to human health if the bacteria enter a building water distribution system, find conditions conducive to their growth, and then become aerosolized. Testing the building or on-premise water for L. pneumophila is important to ensure the facility’s water management plan is controlling this risk once the water enters the property.15

It’s a good idea to involve your local water provider in your water management planning and execution. For example, you can request to be notified about main breaks and other water-quality events in the water distribution system that could temporarily increase the risk caused by water coming into your property. Some utilities are also starting to test their treated distribution water for L. pneumophila in support of customers’ water management plans. Finding a low level of L. pneumophila during routine monitoring provides the utility with valuable information and an opportunity to adjust its disinfectant strategy or add additional steps, such as flushing, to part or all of their systems.15

Although there are no national regulations that require Legionella testing in the U.S., it is considered best practice to test for Legionella in buildings with identified risk factors. As the American Industrial Hygiene Association’s 2015 guidance document states, “Environmental monitoring that includes sampling for viable Legionella is essential to validate the effectiveness of control measures in eliminating or minimizing Legionella growth.” Risk factors include buildings with complex water systems, cooling towers, decorative fountains, humidifiers, and central hot water systems, as well as buildings that house high-risk populations, such as long-term care facilities or retirement communities.16

The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Standard 188, Legionellosis: Risk Management for Building Water Systems, is the only ANSI-accredited industry standard for reducing Legionella risk in the U.S. ASHRAE Standard 188 and the accompanying ASHRAE Guideline 12, Minimizing the Risk of Legionellosis Associated with Building Water Systems, recommend all water management plans have a validation step and that the results of regular validation are documented and reviewed. Routine testing for L. pneumophila meets this requirement.

Healthcare facilities provide services to people who are at increased risk for contracting Legionnaires’ disease: patients aged 50 or older, those with heart or lung issues, former smokers, and those who are immunocompromised. Therefore, regular monitoring is important to protect public health. Monitoring is essential for validating control measures and verifying that controls remain effective. Results can identify environmental sources that can cause Legionnaires’ disease: medical equipment, therapy pools, and ice machines, in addition to cooling towers and hot- and cold-water distribution systems in buildings.

Cooling towers are often associated with large outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease in communities. These “wet air conditioning systems” cool the air by using a process that involves extensive contact between water and air, which creates aerosols. When Legionella are present in these systems, the aerosolized bacteria are easily spread, sometimes over large distances. Legionnaires’ disease cases have been identified as far as 3 k away from the identified cooling tower source. Air-conditioning units that use water to cool the air in hotels and office and commercial buildings can also put people at risk for Legionnaires’ disease. Legionella pneumophila has been the most highly recovered Legionella species in cooling towers in multiple studies in the U.S. and around the world. To date, Legionella pneumophila has also been the only species of Legionella linked to a cooling tower outbreak in published studies, internationally as well as in the U.S.18,19

Ninety seven percent of all cases of Legionnaires’ disease are caused Legionella pneumophila.3 The bacteria are transmitted when contaminated water is aerosolized (e.g., water sprays, jets, mists from air vents, showers, hot tubs, fountains). People become infected by inhaling or, in rare cases, aspirating the bacterium. Those most at risk of infection are older adults, people with heart or lung issues, former smokers, and people who are immunocompromised.

Likelihood of illness depends on the concentration of the bacteria in the water source; the production and dissemination of aerosols; host factors, such as age and preexisting health conditions; and the virulence of the strain of Legionella. The dose required to produce infection can be assumed to be low for susceptible people, as illnesses have occurred after short exposures and at distances of 3 km or more from the source of outbreaks.17,18,21

Yes, any site where people at higher risk may be exposed (hotels, hospitals, long-term healthcare facilities, cruise ships) should regularly check their engineered water system for the presence of Legionella bacteria. Regular monitoring and appropriate control measures may prevent cases of Legionnaires’ disease. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 9 out of 10 Legionnaires’ disease cases could have been prevented with better water management programs.17

Indeed, France requires routine monitoring for L. pneumophila in a wide range of buildings, and France’s rate of Legionnaires’ disease increased at only half the rate of Legionnaires’ disease case increases across Europe between 2013 and 2017.4

Although most infections are caused by serogroup 1, all 15 serotypes of Legionella pneumophila are pathogenic. L. pneumophila serogroups 2–14, and specifically serogroups 5 and 6, have all caused Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks in the U.S. or Canada. Overall, Legionella pneumophila is responsible for 97% of cases and 100% of deaths from outbreaks of the disease.1–3,8–11,13,22

References

- Benedict KM, Reses H, Vigar M, et al. Waterborne disease outbreaks associated with environmental and undetermined exposures to water—United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 66(44);1222–1225. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6644a4

- Beer KD, Gargano JW, Roberts VA, et al. Outbreaks associated with environmental and undetermined water exposures—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(31):849–851. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6431a3.htm. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- Surveillance report: Legionnaires’ disease in Europe (Years 2009-2015). Stockholm, Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; published 2011-2017.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance Report: Annual Epidemiological Report for 2017: Legionnaires’ Disease. Stockholm, Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2019. www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/AER_for_2017-Legionnaires-disease_0.pdf. Published January 2019. Accessed April 19, 2019.

- Racine, P., Smith, P., Elliott, S. Key Factors in Legionella Control and the Positive Impact of Regulations for Water Treatment Professionals. Paper presented at: Association of Water Technologies Annual Convention 2018, September 28, 2018, Tampa, FL.

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 11731:2017: Water Quality—Enumeration of Legionella. www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:11731:ed-2:v1:en. Accessed April 19, 2019.

- Kimura S, Tateda K, Ishii Y, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Las quorum sensing autoinducer suppresses growth and biofilm production in Legionella species. Microbiology. 2009;155(Pt 6):1934–1939. doi:10.1099/mic.0.026641-0

- Beer KD, Gargano JW, Roberts VA, et al. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks associated with drinking water—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(31):842–848. www.cdc.gov/MMWR/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6431a2.htm. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- Benedict KM, Reses H, Vigar M, et al. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks associated with drinking water—United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66 (44):1216–1221. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6644a3

- Hlavsa MC, Roberts VA, Kahler AM, et al. Outbreaks of illness associated with recreational water—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(24):668–672. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6424a4.htm. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- Hlavsa MC, Cikesh BL, Roberts VA, et al. Outbreaks associated with treated recreational water—United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:547–551. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6719a3

- Kruse EB, Wehner A, Wisplinghoff H. Prevalence and distribution of Legionella spp. in potable water systems in Germany, risk factors associated with contamination, and effectiveness of thermal disinfection. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(4):470–474. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.10.025

- Donohue MJ, King D, Pfaller S, Mistry JH. The sporadic nature of Legionella pneumophila, Legionella pneumophila Sg1 and Mycobacterium avium occurrence within residences and office buildings across 36 states in the United States. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;126(5):1568–1579. doi:10.1111/jam.14196

- World Health Organization. Legionellosis [fact sheet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/legionellosis. Published February 16, 2018. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- LeChevallier M. Monitoring distribution systems for Legionella pneumophila using Legiolert. AWWA Wat Sci. 2019;1(1):e1122. doi:10.1002/aws2.1122

- Kerbel W, Krause JD, Shelton BG, Springston JP. Recognition, Evaluation, and Control of Legionella in Building Water Systems. Falls Church, VA: American Industrial Hygiene Association; 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legionnaire’s disease. Vital Signs. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2016-06-vitalsigns.pdf. Published June 7, 2016. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- Facts about Legionnaires’ disease. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control website. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/legionnaires-disease/facts. Updated June 26, 2017. Accessed April 19, 2019.

- Llewellyn A, Lucas C, Roberts S, et al. Distribution of Legionella and bacterial community composition among regionally diverse US cooling towers. PLoS One. 2017; 12(12):e0189937. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189937

- The European Guidelines Working Group. European technical guidelines for the prevention, control and investigation of infections caused by Legionella species. https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/Legionella%20GuidelinesFinal%20updated%20for%20ECDC%20corrections.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed April 19, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legionella—Causes, how it spreads, and people at increased risk. www.cdc.gov/legionella/about/causes-transmission.html. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- Bedard E, Levesque S, Martin P, et al. Energy conservation and the promotion of Legionella pneumophila growth: The probable role of heat exchangers in a nosocomial outbreak. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(12):1475-1480. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.205

- Racine P, Ham J. Legionella regulations—rejoice or run for the hills? Paper presented at: Legionella Conference 2018; May 10, 2018; Baltimore, MD.